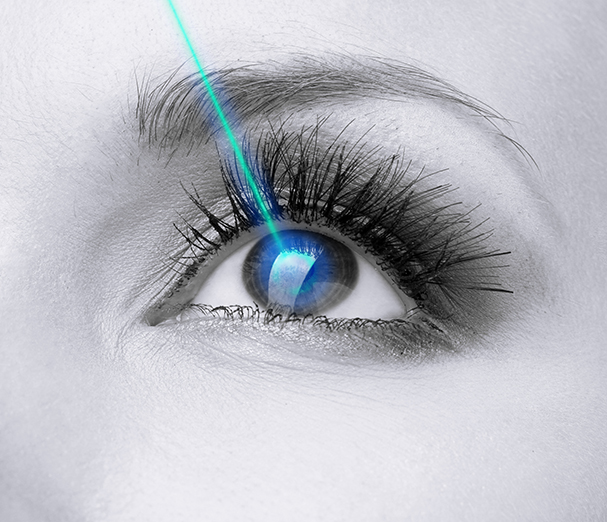

HBCU, Howard University College of Medicine graduate, Patricia E. Bath, an ophthalmologist who took a special interest in combating preventable blindness in underserved populations and along the way became the first black female doctor to receive a medical patent. Indeed, The United States Patent and Trademark Office, which has singled out Dr. Bath’s achievement several times over the years, said in a 2014 news release that her work had “helped restore or improve vision to millions of patients worldwide.”

In an interview for the Changing the Face of Medicine exhibition, Dr. Bath described her “personal best moment”: using an implant procedure called keratoprosthesis to restore the sight of a woman in North Africa who had been blind for 30 years. “The ability to restore sight is the ultimate reward,” she said.

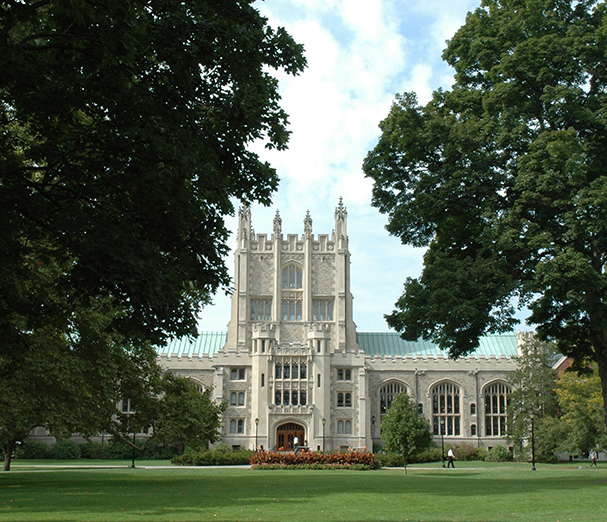

Dr. Bath studied chemistry and physics at Hunter College in Manhattan, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1964, and received her medical degree at Howard University in Washington in 1968. Following her graduation from the Howard University Medical School she went to New York to do an internship at Harlem Hospital and a fellowship at Columbia, setting the stage for her insights into the racial disparities in statistics on blindness and her proposals for community ophthalmology.

“Disproportionate numbers of blacks are blinded by preventable causes,” Dr. Bath wrote in a 1979 paper in the Journal of the National Medical Association. “However, thus far, no national strategies exist for reducing the excessive rates of blindness among the black population.”

After Dr. Bath relocated to Los Angeles, she became the first woman on the faculty of the department of ophthalmology at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at U.C.L.A. She was, she said, offered an office in the basement next to the animal laboratory. “I said it was inappropriate and succeeded in getting acceptable office space.”

In conducting the research that led to her first patent, Dr. Bath took a sabbatical in Europe in part to escape racism and sexism in the American academic and scientific worlds. Even when she succeeded, her achievement was not universally celebrated. “There was not acceptance,” she told Time, “and in some instances there was anger that petite moi, little me, had indeed shattered the glass ceiling, had a scientific breakthrough.”

“The narrative of surprise — it has to change,” she told the magazine. “I realize that when I achieve these things it helps what other women, and other people of color, black women, can do. But keep in mind: I never had any doubts.”

By 1983, Dr. Patricia Bath had helped create the Ophthalmology Residency Training program at UCLA-Drew, which she also chaired—becoming, in addition to her other firsts, the first woman in the nation to hold such a position.

![]](http://www.hcienterprise.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/pc.jpg)